Editor’s note: This post originally appeared on Publishing Trendsetter.

Earlier this year, France made publishing news headlines when its court ruled ebook subscription services like Kindle Unlimited illegal. The law cited was the Lang Law, which gives publishers the exclusive right to set the price of a book. Retailers are not allowed to discount more than 5 percent from this set price.

You may be thinking, A measly 5 percent? Here in the United States, we’re used to seeing 50 percent or more slashed off our books. Price fixing in general is regarded as suspect and is, in fact, legally so. The Department of Justice sued Apple and the five Big Six publishers when they tried to set ebook prices through agency pricing. (To clarify, agency pricing itself isn’t illegal; that the companies coordinated with each other to set prices is.)

But in other parts of the world, price fixing is even welcomed— especially when it comes to books. Many countries have a fixed book price (FBP) system like France’s Lang Law.

An FBP system is an arrangement between publishers and retailers that establishes a (more or less) fixed price for each book sold in that market. Because retailers can’t compete on price, big box stores and online retailers have less advantage in the market, and independent bookstores have more opportunity to thrive. This diversity in the distribution network, in turn, is supposed to promote bibliodiversity. An FBP system assumes that variety— in booksellers and in books— is necessary for nurturing a healthy reading culture.

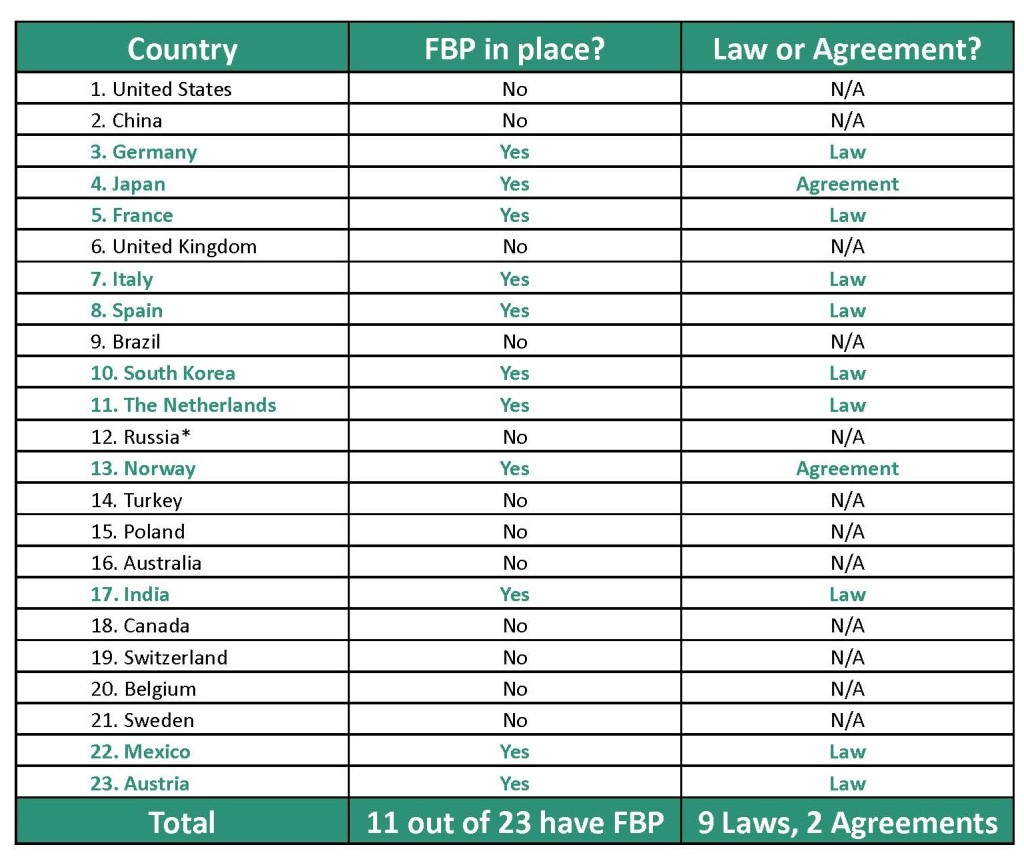

In practice, FBP systems look different from country to country. In some countries, FBP is a law; in others, it’s a trade agreement. Other variables include duration, discount rate, and format. For example, how long after publication does the fixed priced apply? What, if any, is the maximum discount allowed? Are ebooks included?

Among countries with a major publishing industry, FBP is somewhat common. Below is a list of the 23 largest book markets (according to the Frankfurt Book Fair Business Club) and their current FBP practice (collected from various sources).

But this doesn’t necessarily reflect the history or the future of FBP in these countries. Sweden and Australia, for example, were earlier adopters, but both abolished their FBP systems in the 1970s. Switzerland worked to revive their FBP system, until it failed in a referendum in 2012. Mexico signed an FBP law in 2008, but without provisions for enforcement it hasn’t done much except create chaos. Poland drafted a bill for an FBP system in late 2013; more than two years later, it’s still in the works.

What makes some countries say no and others say yes to fixing their book prices?

The United Kingdom pioneered the FBP system, but doesn’t have one anymore. According to a report by the International Publishers Association, FBP began in the UK as pricing agreements made between publishers and booksellers in 1829; a nationwide Net Book Agreement came into effect in 1900. Then, just short of 100 years old, the Net Book Agreement collapsed in 1995 after major publishers and retailers withdrew. In 1997, it was finally ruled illegal and anti-competitive. By then, one writer for The Guardian reflects, the UK had fully converted to free market capitalism and price had become first priority.

The collapse of the Net Book Agreement has made the British book market more like ours, as predicted by the publisher John Wiley & Sons in 1996, in that it has narrowed. British independent bookstores are on a steep decline (after more than 500 closures in the past decade, the total number of stores dropped below 1000 last year). Though the loss of FBP isn’t the only cause, the worrying situation overall has prompted discussions about bringing the Net Book Agreement back in the UK.

France, meanwhile, continues to be FBP’s most brilliant champion. In 1924, France became the first to put book pricing in the hands of the government, according to unverifiable information in the IPA report. The Lang Law, which quickly inspired similar systems across Europe, was signed in 1981. The law has since continued to shape and define the French book market. In 2011, it was updated to include ebooks, which is why Kindle Unlimited and other subscription services could be declared illegal. And in June 2014, it spurred another “Anti-Amazon Law,” which prohibits online retailers from combining the 5 percent discount with free shipping. (Amazon was quick to find a way around it, though— make the shipping fee 1 cent!)

Clearly, France takes great initiative to preserve a certain environment for books, and it shows. France boasts over 2000— 3000 if you include small ones— independent bookstores, according to a recent New York Times article. And publishers, like this editor at Belfond in a Publishers Weekly feature, seem encouraged by their strong presence in retail.

Paris-residing writer Pamela Druckerman provides insight into the radically different approach. She clarifies in her New York Times Op-Ed that “what underlies France’s book laws isn’t just an economic position— it’s also a worldview.”

In France, “‘books are seen as a cultural rather than a commercial product,’” echoed a Penguin Random House executive in a Publishing Perspectives article. And, one editor at Gallimard explained, since the Revolution, “‘the French state has always considered that culture is not a private matter.’” The government actually classifies books as an “essential good,” as Druckerman and others have pointed out.

What’s more, this worldview isn’t exclusive to France. Other FBP-practicing countries uphold similar ideals about books and reading. Germany— the proud birthplace of the printing press and numerous intellectual movements, as the President of the German Publishers and Booksellers Association reminded Publishing Perspectives— also views books as cultural first, commercial second. Books don’t have to be bestsellers to have merit, and people seem to know that Buchpreisbindung (Germany’s FBP law) is in the best interests of such not-so-bestselling-but-equally-valuable literature.

Japan may not frame its ideals about books and reading in historical legacy the way its European peers do, but it still shares the same understanding. Books are described as a basic resource that contributes to the country’s cultural well-being on the Japan Book Publishers Association’s website. And the Resale Price Maintenance System (Japan’s FBP agreement), it continues, not only secures space for small retailers and a wide variety of literature, but also ensures that books remain equally accessible across the urban-rural divide.

What FBP yeasayers seem to have in common is a commitment to books as a cultural asset. They forgo the short-term convenience of buying cheap books, in hopes of promoting the long-term health of books, publishing, and reading.

This worldview is hard to reconcile with the consumer-first mindset that tends to be strong in the United States. Since the DOJ lawsuit, there have been even more heated discussions about FBP in the American book market. Opinions seem split along producer-consumer lines, with publishers wanting to protect the value of their products and readers wanting to maintain fair and easy access to books.

Given its history with agency pricing in ebooks, there’s little reason to think the United States will ever see an FBP system like those seen in France, Germany, and Japan. And with independent bookstores making an impressive comeback in recent years, there’s even less incentive for Americans to entertain the idea, let alone the practice.

As it turns out, you don’t even need to open a book to think about what’s going on elsewhere in the world. Flip it over. Look at the price tag. And ask— So really, how much did that book cost?